Mary Bliss Parsons: The Witch of Northampton

Mary Bliss Parsons: The Witch of Northampton

by Karen Vorbeck Williams

First published by The New England Historical Society

The year 1656 wasn’t the first time Mary Bliss Parsons of Northampton was accused of witchcraft. Nineteen years later, in 1675, she was indicted for witchcraft and imprisoned for 10 weeks in Boston to await her trial. Some of the magistrates who sat in judgment of her went on to hear the horrific Salem witchcraft trials of 1692-3, the last hurrah for New England’s witch hunters. They had recognizable names: Thomas Danforth, Simon Bradstreet, William Stoughton, and then-governor, John Leverett.

Simon Bradstreet

William Stoughton

Governor John Leverett

MARY BLISS PARSONS

Mary Bliss was born in England in about 1627, most likely in Painswick Parish, Gloucestershire. She came to Mount Wollaston (now a part of Quincy) in the Massachusetts Bay Colony around 1635 at the age of about eight. She sailed with her parents and four elder step-brothers.

By 1640 they, and many others, had followed the great Puritan divine Thomas Hooker to Hartford in Connecticut Colony and belonged to the first group of settlers there.

Thomas Hooker and his people

Many extant records and a number of depositions explain the accusations of witchcraft against Mary. When the whole story came out it all came down to the jealousy of one woman. Sarah Lyman Bridgman convinced other townsfolk that Mary Bliss Parsons—with the help of the devil—had caused their hard luck, even the deaths of their babies.

Witches bringing children to Satan

Mary wasn’t afraid to take her complaints and opinions right to the source of her grievance. If she paid you to weave some yarn and you delivered it full of flaws, she wouldn’t stand for it. If you borrowed the family’s team of oxen to plough a field and she saw you whipping and mistreating them, she would march across the field and give you a talking to.

JOSEPH PARSONS

Legend says Mary Bliss was a great beauty. To make herself even more enviable she married Joseph Parsons in 1646. He would become the wealthiest man in Hampshire County and, before he died, one of the richest in the territory. Joseph traded furs, owned a retail store and the sawmill and co-owned the first grist mill in Northampton. In 1661, he got a license to keep an ordinary, or tavern, there. He would become the largest land owner in the new settlement of Northfield, and in Boston he bought a house, a wharf and warehouses.

Joseph also served often as selectman and, because he knew the Indians through his trading enterprises, as liaison between the natives and the townsmen.

Though it was written that Mary Parsons was ‘possessed of great beauty and talents.’ She was not very ‘amiable,’ she had ‘haughty manners’ and was ‘exclusive in the choice of her associates.’ So, there she was, beautiful and rich with a mind of her own to speak.

As if that wasn’t enough to annoy all the other goodwives in town, she had an astoundingly successful birthrate. In the 17th century, many women died giving birth, and many children did not survive childhood. For 25 years Mary got pregnant just about every two years. Her last child was born when she was a grandmother. She had 11 children, including two sets of twins. All but two of her children survived to adulthood. In a time when male children were valued above females (males were needed to run the farm) her first six babies were boys and then came five girls. It was just as if she had said, “Joseph, I have given you all the help you need. Now I will help myself.”

SARAH LYMAN BRIDGMAN

Sarah Lyman Bridgman was convinced Mary’s good fortune was a gift from the devil. Her gossip spread from town to town in the Connecticut River Valley. Many of Sarah’s friends and neighbors listened and wondered. They told stories. Several people saw Mary walking out at night wearing nothing but her shift. One man followed her and saw her walk on water. When he reported her, he said her clothes were not wet.

Because of her night walks, her husband installed a lock on the door to their house. He later complained to a friend that no matter where he hid the key, Mary would find it and go out in the night. Frustrated, Joseph forced her into the cellar and locked her in for her own safety. Alone and terrified Mary reported seeing spirits fly at her in the dark. All this happened during the early years of their marriage while they lived in Springfield during a witch scare. Another woman—also named Mary Parsons and her husband Hugh Parsons were suspected of witchcraft. The year was 1651.

Mary’s mother, Margaret Hulins Bliss’ house at Springfield. Photo taken in the 19th century.

While in church, probably during a sermon about doom and the devil’s presence in town, two ‘bewitched’ children (the minister’s young daughters) fell screaming to the floor under a ‘witch-induced’ spell. Overcome by fear, Mary joined them on the floor clutching at her throat and crying out in terror. She had to be carried home. Mary Bliss Parsons’ strange behavior in Springfield aroused the suspicions that followed her to Northampton.

No one knows why she was so disturbed during this time. She did lose both her second baby and her father in 1650 and then there was the witch scare. Witchcraft was a real thing back then.

Thomas Cole’s painting of the Oxbow on the Connecticut River near Northampton, Massachusetts

JEALOUSY

Both Mary and her enemy Sarah, had come of age in Hartford. Mary’s father, an average yeoman, had only six acres of land. Sarah’s much better off father had 30 acres. After their marriages, both young women moved with their husbands to Springfield. Some years later, when Mary’s husband decided to join in the settlement of Northampton in Massachusetts, Sarah and her family soon followed.

Poor Sarah had little good fortune. Her husband was not rich and not much involved in town government. He served as constable for a short term, and the other positions given him were unimportant. Sarah had eight births but only four children survived infancy—three girls and one boy. Three boys and one girl died at two months, four months, six months and nine months.

Sarah accused Mary of causing her only son a grave injury. He had gone into a swamp to fetch a wandering cow when ‘there came something and gave him a great blow on the head…and going a little further…he stumbled and put his knee out of joint.’ The healing did not go well even after the knee was set and, as a result, he suffered a lot of pain. In his delirium ‘he cried out that Goody Parsons would pull off his knee’. And then from his bed he said ‘there she sits on the shelf…there she runs away and a black mouse follows her.’

Sarah’s stories about Mary’s witchery spread to both Springfield and Northampton. When Joseph Parsons heard the gossip, he sued Sarah for slander and won his case, further damaging Sarah’s reputation.

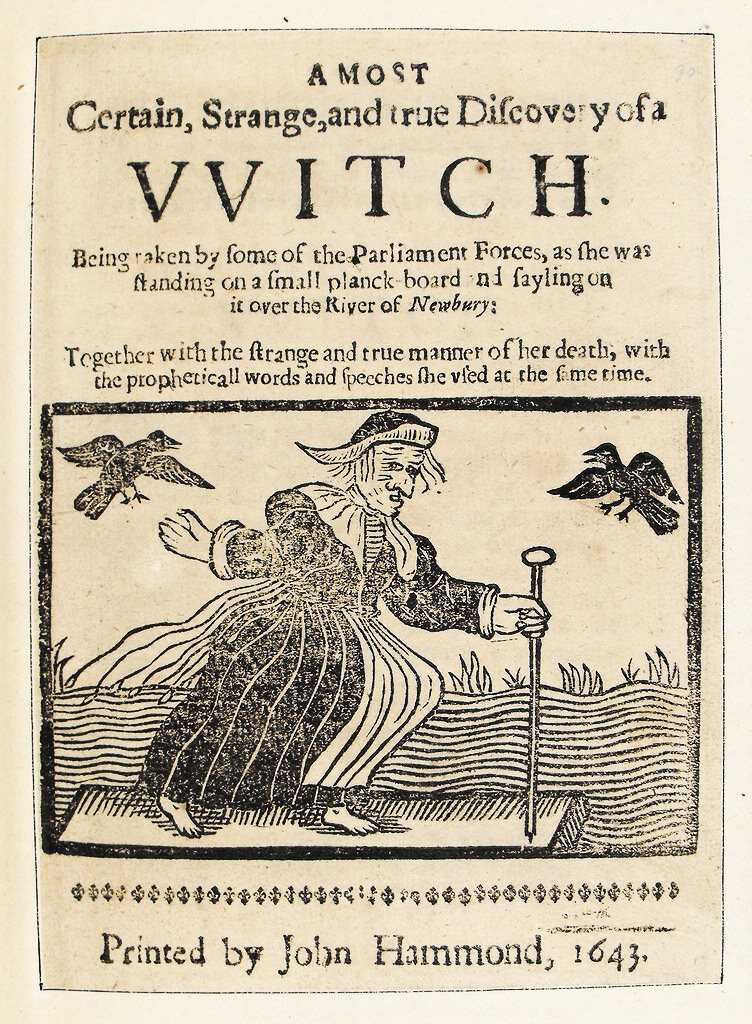

A MOST Certain, Strange, and true Discovery of a WITCH. Cover of a small book by John Hammond, 1643.

THE TRIAL

Sarah died in 1668 at about the age of 47, but the animosity she carried toward Mary Parsons lived on. In 1674 Sarah’s daughter, Mary Bridgman Bartlett, a young wife and the mother of her first child, died under suspicious circumstances. People said ‘she came to her end by some unlawful and unnatural means…by means of some evil instrument.’

Her husband, Samuel Bartlett, and father, James Bridgman, saw to Mary Parsons’ arrest, indictment, imprisonment and trial on May 13, 1675.

Depositions and testimony of this trial have been lost, but historians assume that many of the same charges brought against Mary during the slander trial of 1654 were aired along with the new charge of the murder by witchcraft of Mary Bridgman Bartlett.

Mary testified to her innocence and that she had committed no crimes. She said, “The righteous God knows of my innocency—with whom I leave my cause.”

A jury of 12 men found her innocent, and the governor, and magistrates of the Court of Assistants allowed her to go free. She went home to care for her children, the last of whom was only two.

Karen Vorbeck Williams, the author of this story, is the award-winning author of My Enemy’s Tears: The Witch of Northampton, The House on Seventh Street, and Pretty: A Memoir.